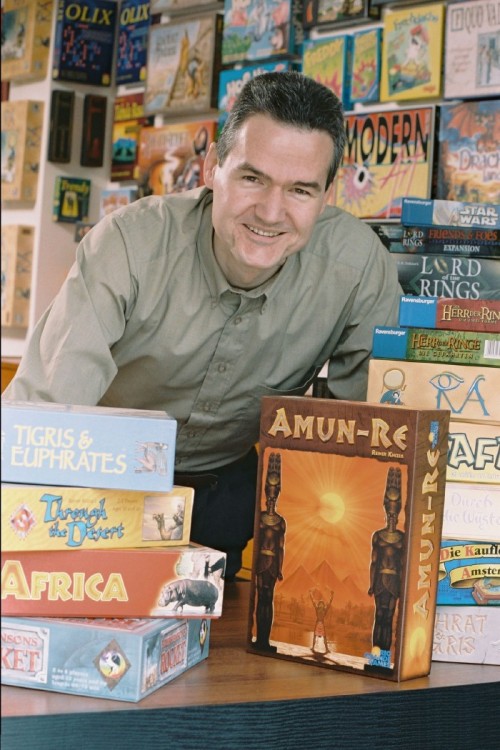

Reiner Knizia needs no introduction. As the most prolific game designer in the world today, you’ve almost certainly encountered his games, of which there are many. During our conversation, I was struck with not only how kind and funny he is, but also how much wisdom he’s amassed over the years, wisdom that he was more than willing to share with me.

And now I’m going to share it with you.

This post has affiliate links, which directly support Andhegames.com at no extra cost to you. If you have any questions about anything recommended, let me know. – Andrew

Tell us about yourself – Who are you? What do you do?

This is my third life. My first life was at university where I really enjoyed teaching, studying, and researching mathematics. My second life was in banking and I.T., where you work for the big company, get big responsibilities, and also get involved in big politics, which I never enjoyed. My last job was running a big mortgage company here in the U.K., with about 300 people working there.

Then I decided to jump into my third life – it’s been quite a while ago now – to do games. Of course I’ve done games on the side all the time – they’ve always been my love and my hobby – then I got braver and had some successes, and I knew that I wanted to do this. Now I’m a full-time game designer.

What tabletop games (including digital board/card games) are you playing most right now?

Two answers: I’m playing every day, because designing games is essentially experiencing the fun of games, therefore [it’s important to be] playing them. But whenever I have an opportunity to play, I play my new designs. There are sixty drawers in my office, and most of them are filled with new designs, so there are lots of ‘monkeys’, as I call them, who want to be fed. This means that I rarely play other people’s games. I do play them, and my play testers bring new designs they think are remarkable, and we look at them – but that’s not the normal day-to-day business.

One fact that we probably don’t know about you:

I’m a thief. When I fly in airplanes, I steal the cutlery. I have a big collection of cutlery from the different airlines. And I’m running organized crime, because I ask other people to steal for me when they fly on certain planes. I have several hundred collectible pieces now. Of course, now we’ve stolen all of it, because the airlines have run out of cutlery, and they give you plastic instead of the metal ones.

(I want to be part of a Reiner Knizia crime ring! –A)

What are you naturally good at that helps you in your work?

That’s a very difficult question. I think every game designer has his or her own strengths – some people come from the graphics side, some people come from the storytelling side – I think I come from the scientific side. Mathematics help me create models, and my perfectionism helps me really test everything in detail.

But calling it a strength is a dangerous thing, because as soon as you call something a strength, you’re bound to overdo it – and then you turn your strength into a weakness. What I have learned over time is to not rely on one strength, and not to have one fixed methodology when designing games. Designing games is not a science where you have a specific method that you always repeat. As a designer, my ambition is to create something new and innovative every time, and it’s been my experience that I should start with something new and innovative – a new character, a new technology, a new material – because, although there’s no guarantee, that’s my best chance to come up with something innovative at the end, and not trample along the same path all the time.

So, in a way, what I’ve learned is to be wary of my strengths.

What are you not naturally good at, that you’ve learned to do well anyway?

It’s funny – some people criticize my games for being abstract and not very thematic, and I’ve learned to be careful with my models, which in the past usually started from the thematic motivation, so I don’t forget to communicate the theme.

The theme would be there, but I would very much bring it down to its bones – its essentials. I could still see the theme and interpret a lot of the actions, but sometimes the communication process to the publisher and the players causes the theme to be lost, so that players no longer know how to interpret the individual actions. I’m now putting more emphasis on communicating the theme how I see it. That’s a challenge, because I do have a scientific approach: I don’t like to tell a vast story with lots of details, or make players read long, complicated rules. [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=”@andhegames”]I try to make games with very few principles, so they’re natural to play.[/inlinetweet] Once you understand the basic principles, you can almost derive what to do in various situations. But this does mean that the rules are short, and you’ve got to be careful that you don’t lose the theme as you condense the rules.

Do you generally approach a game from a thematic or mechanical angle?

In the early days, I usually started from the theme: I’d have a theme that really fascinated me, and then I’d try to transfer that theme into a game system. Even when people though that the theme is missing, it was the starting point, as we’ve just discussed. But now I try to avoid this – I’m essentially trying to feel uncomfortable in the design process, because as long as I walk along the comfortable path, the innovation is not as strong as when I’m uncomfortable.

I was very uncomfortable when I did The Lord of the Rings, because you want to be true to the story and the spirit of the book, and you know that all of the fans have a certain viewpoint: therefore you must be a hobbit; therefor you cannot compete with each other; therefore you need to cooperate with each other; one thing leads to another, and suddenly you end up having to make a cooperative game that goes through this enormously big book, a game that you can play in an hour. That was an uncomfortable situation in the positive sense: it forced me to think in a new way, and therefore come up with something innovative.

Describe your process (or lack thereof) when making games. How do you reach your final product?

Essentially there are three stages: there is the initial stage where there is nothing material yet: it’s closing your eyes and looking into the new world, and trying to have all the different aspects of the game flow together. This very often would [take place] in discussions. I have a good dozen people who are very experienced players in my core playtesting group; we have a lot of discussions, particularly when a new theme or a new challenge comes on the table. This brings the best out for the design.

We really don’t start implementing things until we have a very clear idea about how the game should look. Of course, in your mind it always works wonderfully well, and then your first prototype shows you reality.

In the second phase, which is a much, much longer phase, you make a prototype, and quite a number of games die after the first prototype. You think something will work, but then you realize that there are certain flaws, so we cut our losses, and that’s fine. The disasters are when you try to push it and push it, and you spend many, many days on the design, and then in the end you have to give up.

Otherwise, it’s just the normal process of selection and finding out what works. Assuming that the idea is feasible, then what follows is a very long play testing process. We play every day, and initially between the play testing sessions there’s a lot of rework, and radical changes from one session to another. This converges more and more into a stable situation, where we then do the fine-tuning, where there’s not much to do in between sessions. We change a few parameters, a few values, and if we don’t have any more ideas on how to change it, and we still believe the game is good, then we enter the third phase.

In the third phase, I leave the game for a month or two, so that I get a bit of a distance to it, and then we play it again once or twice. We just did this last night with a game that we just kind of finished in August. We looked at it, and we saw that it was still absolutely fine. Then we make a very nice prototype with very nice materials, and we have a ruleset which is written for the publisher, not for the public, because the publishers have their own style, and then we present it to the publisher.

. . .

[…] the interview with Mr. Knizia! […]

Wonderful insight. Thank you.

[…] How Reiner Knizia Makes Games […]

I almost fell off the chair laughing when he admits he is a thief and of course a tableware thief… If I didn’t have my reading glasses on, I might have read tabletop thief!

These are all great questions and I can’t wait for the 2nd part. I like most the statement that innovation comes out of being uncomfortable. I have used constraints in the past as ways to make myself uncomfortable, whether this is production cost or a mechanical constraint. What are some other ways to make yourself uncomfortable in your own work?

In my experience, constraints are powerful creativity-sparking tools. A few ideas that have worked for me:1. Publicly commit to a project that you’re unsure if you can do.

2. Commit to a routine for a certain period of time: e.g. I will write 1000 words/make a mini game/draw a picture/etc every day for a month, no matter what. Understand that crappy work is better than no work.

3. Push the edges of your art. Don’t land in the middle. The edges are where innovation is: try breaking the rules, just to see what happens. Choose an edge (simple/complex/cheap/expensive/ugly/beautiful/disposable/long lasting/corny/dark) and stick to it. Push it all the way.

🙂 Have fun.

Love the advice to publicly commit to things and I have found this super effective. Thanks for the reply!

[…] is part 2 of the fantastic conversation we had. Check out part 1 if you haven’t […]

[…] 2 of the fantastic conversation we had. Check out part 1 if you haven’t […]

[…] games is not a science where you have a specific method that you always repeat.” – Reiner Knizia “A designer should work out what people enjoy about their game and then organize the rules […]

[…] might be interested in learning how Reiner Knizia makes […]